Analysis of Auteurs

Chris Cunningham

Aphex Twin

In the music videos produced by Cunningham for Aphex Twin, many of Cunningham's recurring themes, techniques and symbolism rise to the fore. To address this, I compared and contrasted two videos from within Cunningham's work with Aphex Twin.

More common with the auteur movement, both the "Come to Daddy" and "Windowlicker" music videos note Cunningham as the director in the opening, and, as both videos open, it is clear that Cunningham has maintained an almost film-like approach to his videos (something which is then reinforced by the use of end credits superimposed over repeated, tinted clips of the video at the end of "Windowlicker").

At the opening of "Come To Daddy", Cunningham's use of colour filters are immediately obvious, a dark blue tint applied to all clips in the video. Indeed, he uses a similar technique in window licker, instead opting for a non-coloured, dark tint on what otherwise might have been a sunny day. The use of this technique in both sets a mood for the videos, the darkness connoting to the equally dark themes used within them.

Cinematography and editing are also key in creating the mood in these videos. "Come To Daddy"'s editing pace begins slowly, allowing the tone and scene to be established and giving room for the tense build up of the loose narrative and editing speed. In this, time is taken to construct feelings of unease. The long, establishing shots of the high rise flats are filmed at a twisting, canted angle, signifying the dysfunctional nature of the video, and there is a

sense that the old woman and her dog are being watched, built firstly by the low-angle shots, looking up at the woman as if from the possessed television's point-of view. It is then built by an additional shot/reverse shot sequence between that of a moving spectator (backlit and thus silhouetted, masking any features and causing the figure to be interpreted as dark and mysterious), and the reverse shot of the person's evident location, revealing nothing except an ominous dark space in the wall, heightening the feeling of unease and mystery. The editing then begins to speed up with the appearance of the strange children, and a sense of panic is conveyed through the use of quick, repetitive shots (the child running a stick along the fence, for example), an ever more shaky handheld camera technique, whip-pans and dark lighting, causing disorientation and an unsettling atmosphere, especially when combined with comparatively long shots of the demonic television, emphasizing and dominating the hellish themes.

The use of shots to enforce a theme is used to similar effect in "Windowlicker". Although it runs at a generally much slower editing speed (particularly at the beginning, where the dramatized opening

sequence is constructed of very few shots, all very long takes), time is still spent on establishing the dominant themes, in this case the transformation of women from the sexualised representation expected of videos (and noted as a norm of music videos by Goodwin), to the

grotesque. Indeed, once transformed, what might previously have been considered voyeuristic scenes in the limo are now made all the more repulsive by the time taken on the shots depicting romantic/sexual advances between the male artist and the strange women who also have

his face, using slowly zooming long shots and then a series of shorter shots to compile a series of images to shock and repulse and generally build a highly entropic theme. This is continued further by another transformation of a woman later in the video into a deformed creature which then breaks up long, sexualised shot sequences, at one point slowly gliding towards the camera, made-up and danced around in what can be interpreted as a mocking comment on how mass media is centred around the male gaze (as noted by Laura Mulvey - 1975) and how women are overly sexualised and glamourised.

In "Come to Daddy", similar use of post-production image warping (and the costume aspect of

mise-en-scene) is used for unsettling effect. Within the theme of juxtaposing innocence with the strange and demonic (the old woman and the demon, for

example), Cunningham includes children, normally a stereotypical symbol of innocence, with the grinning heads of the artist instead, menacing members of the public, and looking after the demonic television depicting, too, the warped image of the artist. It is notable that the use of

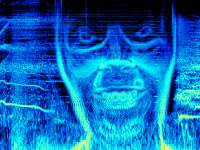

facial expression appears beyond Cunningham's partnership with Aphex Twin - Bjork's "All is Full of Love" includes a computer-animated robot imposed with the artist's face, giving what is generally a symbol of inhumanity emotion and feeling instead.It is also interesting that the technical skill extends to the physical embedding of Aphex Twin's demonic face trademark within the frequency spectrum of "Windowlicker", so, when viewed on a spectograph, the face will be revealed.

The final sequence of "Come to Daddy" reveals the video to be loosely illustrative, conforming to Goodwin's theory of video classification. In this, the small, man-faced children gather

around the demon, freed from the television, and still possessing the face of the artist, who gathers them close and appears to embrace them in a father-like role; effectively they have come to their "daddy", the lyrics of the song repeating incessantly "Come todaddy, come to daddy...". At the resolution of the video, this scene is also accompanied by a series of very quickly edited shots, with jump cuts of the demon taken from varying degrees of zoom, and accompanied with shots of black and flashes of light at a speed that is unsettling and disorientating. The illustrative quality of "Windowlicker", however, is apparent much sooner - "Windowlicker" is a rough translation of a French phrase back into English, and is similar to the term "window-shopper"; essentially, it means that a person wants something they can't have, illustrated in the video by the men at the start of the video who attempt to attract the women at the side of the road, only to be rejected. Later, when pursued, they suddenly become ugly and undesirable - whilst from a distance they were desired, but once close up and the truth was revealed, the  "windowlickers" were instead disgusted. In this, it can also be understood that perhaps there is a comment on the superficiality of love and lust; indeed, even the lyrics seem to mock this: though they are in French, the apparent 'language of love', they translate into English as meaningless nonsense ("J'aime faire des craquettes/croquettes au chien" can be translated to either "I like to have sex with dogs" or "I like to make dog biscuits").

"windowlickers" were instead disgusted. In this, it can also be understood that perhaps there is a comment on the superficiality of love and lust; indeed, even the lyrics seem to mock this: though they are in French, the apparent 'language of love', they translate into English as meaningless nonsense ("J'aime faire des craquettes/croquettes au chien" can be translated to either "I like to have sex with dogs" or "I like to make dog biscuits").

"windowlickers" were instead disgusted. In this, it can also be understood that perhaps there is a comment on the superficiality of love and lust; indeed, even the lyrics seem to mock this: though they are in French, the apparent 'language of love', they translate into English as meaningless nonsense ("J'aime faire des craquettes/croquettes au chien" can be translated to either "I like to have sex with dogs" or "I like to make dog biscuits").

"windowlickers" were instead disgusted. In this, it can also be understood that perhaps there is a comment on the superficiality of love and lust; indeed, even the lyrics seem to mock this: though they are in French, the apparent 'language of love', they translate into English as meaningless nonsense ("J'aime faire des craquettes/croquettes au chien" can be translated to either "I like to have sex with dogs" or "I like to make dog biscuits").It can be notable that, whilst rejecting theorists such as Todorov and Propp, this video seems to closely link to the ideas of Branigan - the video begins by introducing its main characters - the men in the car, and understand the current state of affairs through their initial conversation and interactions with the women. We are then introduced to the artist himself, who begins to warp and complicate this initial introduction - this can be seen at the initiating event. The emotional response by the men to the warping of the women throughout the video is that of shock and repulsion, after the initial act of pursuing the women. The apparent outcome at the end is the twisting of women from sexual icons to warped, repulsive figures. Again, the two men appear repulsed, whilst the artist thoughout the video seems to thoroughly enjoy it, and, at the end, adds to the sexual imagery with the drenching of the women with a champagne bottle.

No comments:

Post a Comment